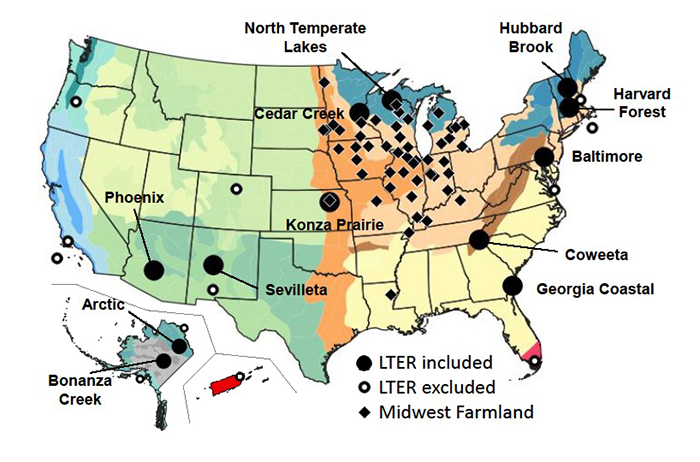

Filled black circles represent LTER sites with arthropod data that were included in the study. Colors on the underlying map delineate ecoregions as defined by the USDA Forest Service.

CONWAY, Ark. (August

11, 2020) — For years now, scientists have warned of a coming “insect

apocalypse” that threatens to wipe out many arthropod species, bringing

significant ecological ramifications, including adverse effects on food

production for human and other animal populations. But exactly what changes are

we seeing in the United States? At this point, the declines do not appear to be

as widespread as feared, according to a new study recently published in Nature

Ecology and Evolution.

Hendrix College’s

Elbert L. Fausett Distinguished Professor of Biology Matthew

D. Moran and University of Georgia Professor of Agroecology Bill Snyder

collaborated on the study with lead author Michael S. Crossley, a postdoctoral

researcher in the UGA Department of Entomology. Numerous undergraduates from

Hendrix, postdoctoral researchers Crossley and Amanda R. Meier from UGA, and

other researchers from the USDA participated in the data analysis. Emily M.

Baldwin, Lauren L. Berry, Leah C. Crenshaw, David H. Nichols, Krishna Patel, and Sofia Varriano formed

the team of Hendrix College student researchers for the project.

The idea for the

study stemmed from a conversation between Snyder and Moran, who attended

college together and over the years have maintained their friendship and

pursued similar research interests. In their discussion, they recalled the U.S.

National Science Foundation’s network of Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER)

sites established in 1980. They posited that examining four decades of data gathered

by this network of 25 monitoring locations across the country could yield significant

findings.

“We thought the

LTER data would be ideal for asking this type of question,” Moran said. “These

study sites were set up in the 1980s to monitor and study ecological processes

across the United States. If, indeed, insect declines had occurred during this

time frame, those monitoring efforts should have detected it.”

The research team

analyzed publicly available databases in the NSF’s LTER network, marking the

first time such information has been gathered into a single dataset to be

examined for evidence of broad-scale density and changes in biodiversity over time.

While some species

and geographical areas showed marked increases or decreases in abundance and

diversity, many remained steady, resulting in very little net change in insect population

trends nationwide. This lack of overall increase or decline was consistent

across arthropod feeding groups, and similar for heavily disturbed versus

relatively natural sites.

“No matter what

factor we looked at, nothing could explain the trends in a satisfactory way,”

said Crossley, the lead author of the study. “We just took all the data and,

when you look, there are as many things going up as going down. Even when we

broke it out in functional groups there wasn’t really a clear story like

predators are decreasing or herbivores are increasing.”

Arthropod data

sampled by the team included grasshoppers in the Konza Prairie in Kansas;

ground arthropods in the Sevilleta desert/grassland in New Mexico; mosquito

larvae in Baltimore, Maryland; macroinvertebrates and crayfish in North

Temperate Lakes in Wisconsin; aphids in the Midwestern U.S.; crab burrows in

Georgia coastal ecosystems; ticks in Harvard Forest in Massachusetts; caterpillars

in Hubbard Brook in New Hampshire; arthropods in Phoenix, Arizona; and stream

insects in the Arctic in Alaska.

Snyder points out

that individual efforts at conservation may be creating ecological improvements

that have a broader influence.

“It’s hard to

tell when you’re a single homeowner if you’re having an effect when you plant

more flowers in your garden,” he said. “Maybe some of these things we’re doing

are starting to have a beneficial impact. This could be a bit of a hopeful

message that things that people are doing to protect bees, butterflies, and

other insects are actually working.”

About Hendrix College

A private liberal

arts college in Conway, Arkansas, Hendrix College consistently earns

recognition as one of the country’s leading liberal arts institutions, and is

featured in Colleges

That Change Lives: 40 Schools That Will Change the Way You Think About

Colleges.

Its academic quality and rigor, innovation, and value have established Hendrix

as a fixture in numerous college guides, lists, and rankings. Founded in 1876,

Hendrix has been affiliated with the United Methodist Church since 1884. To

learn more, visit www.hendrix.edu.