I am proud to be a Japanese-American but have not had a typical Japanese-American

experience, if there is such a thing. I did not, for instance, grow up in a large

ethnic community in a place like Hawaii or California. I did not speak Japanese

at home or live in the midst of an extended Japanese-American family. My father

was an immigrant from Japan, who came to America in the early 1950s to get an education.

My mother was from upstate New York and was of good German and English stock. They

met as postdocs in a lab at Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the rest, as they

say, is history. So, in other words, I had no relatives who were subjected to that

most defining (and scarring) of Japanese-American experiences, mass internment by

the U.S. government during World War II.

In my hometown of Bryan, Texas, there were only two families of Japanese ancestry

and I grew up with very little awareness of what being Japanese-American meant.

I went on to learn Japanese language in college and become a historian of modern

Japan, but an appreciation of my hyphenated-American heritage was slow in coming.

When living in Kansas, where Japanese-Americans are about as rare as they are in

central Texas, I began giving public talks for Asian American Heritage Month, often

because there was no one else in the area willing or able to do so. I served as

the faculty advisor for the Asian-American Student Union, an experience which was

educational and always rewarding for me. And when I was asked to write a book chapter

on the history of Asian-Americans in Kansas, I gladly took on the project, to educate

myself and to share with others a story that had never been told before. Some of

what I learned was unforgettable: for example, when the first dozen Vietnamese refugees

arrived in Wichita in the early 1970s, the local newspaper led with the headline

“Sedgwick County Overrun with Asians.”

Although it clearly had been brewing for a while, a real awareness of being part

of a larger Japanese-American community and history is something relatively recent

for me. In 2011, I had the opportunity to be a member of the Japanese-American Leadership

Delegation, a program sponsored by the Japanese government and the U.S.-Japan Council

to connect Japanese-Americans to their Japanese roots and empower them to assume

more active roles in shaping trans-Pacific relations. For two weeks I traveled around

Japan with a dozen fellow Japanese-Americans from across the United States. From

them I came to appreciate the diversity of the Japanese-American experience and

the complex legacies of wartime internment. Most importantly, though, my time with

them helped me realize the extent to which shared bonds of culture and shared challenges

in American society knit us together as Japanese-Americans despite superficial differences

of age, geography, and personal circumstance.

Thinking more consciously of my Japanese-Americanness (if there is such a word)

has led to some surprising discoveries. For example, last summer I tagged along

with my wife Marjorie to Utah, where she was attending a conference. While she listened

to (and delivered) academic papers, I played the tourist. In between an organ recital

in the Mormon Tabernacle and a pastrami burger (a Salt Lake City greasy-spoon specialty),

I made a pilgrimage to Topaz, one of the ten major Japanese-American internment

camps spread mainly across the desolate expanses of the intermountain West. To call

the Topaz site isolated is a bit like calling Dallas a little warm in August. Located

about 100 miles south of the Great Salt Lake, near the sleepy farm town of Delta

in a broad valley cut by the Sevier River from the Wasatch Mountains, Topaz is not

the kind of place you would just stumble across. On a cloudless summer afternoon,

the grid of dirt roads and a few aging foundations from camp buildings were the

only relics left of the 8,000 Japanese-Americans who lived here 70 years ago. It

was almost perfectly quiet as I walked what once was a barbed-wire perimeter, the

silence broken only by locusts rising from the sagebrush, an occasional hare darting

out in front of me, the flapping of an American flag at a small memorial by the

highway, and the heavy sound of my footfalls. It was beautiful and horrible and

peaceful and disturbing, all at the same time. I drove away with profound respect

for the endurance and resilience of the people (most of whom were U.S. citizens)

imprisoned in such an otherworldly spot and nagged by a certain shame as an American

and a member of a generation that has largely forgotten such a painful chapter in

our history.

I was aware there were two internment camps in Arkansas, as I had a student at

the University of Kansas who wrote a term paper for me about them. But imagine how

surprised I was when I walked into the Mills Center for the first time, late last

October when Marjorie and I were on our introductory tour of the Hendrix campus,

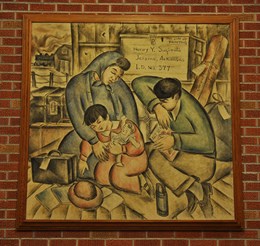

and encountered one of the true masterpieces of Japanese-American internment camp

art. “Arrival at Camp Jerome” is a magnificent oil by Henry Sugimoto, a talented

painter who was born in Japan and studied in Paris before settling in California.

In 1942, he was “relocated” (as the federal government euphemistically called it)

to Arkansas, eventually spending time with his family in both the local camps at

Jerome and Rohwer. Many of

Sugimoto’s

paintings are now held by the Japanese-American National Museum in Los Angeles

and constitute

an intimate visual chronicle of the daily routines and myriad indignities of internment.

I hadn’t even had a chance to ask anyone why there was a Sugimoto high up on

that Mills Center wall before I received a lovely email from Tom Goodwin in the

Hendrix Chemistry Department. Tom was one step ahead of me and sent along a fascinating

1994 article by Robert Meriwether explaining how the painting had ended up at Hendrix.

As many of you will know, Louis Freund, who taught art at the college during the

war, invited Sugimoto to have his only exhibition in Arkansas (at least beyond the

fences of the camps themselves) on the Hendrix campus in 1944. After the show, the

college wisely (but, I imagine, somewhat controversially) purchased one of Sugimoto’s

finest works. It is a testament to the Hendrix community and its enduring commitment

to inclusiveness that, even in a time of war and fear and injustice, the campus

could welcome a Japanese-American artist with talent and a quiet message of resignation,

loyalty, and dignity in distress.

I have a sneaking suspicion that “Arrival at Camp Jerome” might just end up in

the president’s office come June 1. And I know for sure that high on my list of

priorities when I arrive in Conway are visits to the sites of the internment camps

in Jerome and Rohwer and a tour of the new museum (only a year old as of April)

dedicated to their history in the delta town of McGehee. I am proud to follow in

Henry Sugimoto’s footsteps to Arkansas, and even more proud to be joining a community

with a long heritage of embracing difference and a free-thinking culture that is

not afraid to take on even the most difficult of issues.

About Bill

Dr. William M. Tsutsui became the 11th President of Hendrix College on June 1, 2014. He came to Hendrix from Southern Methodist University where he was Dean and Professor of History at Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences.